Driftwood

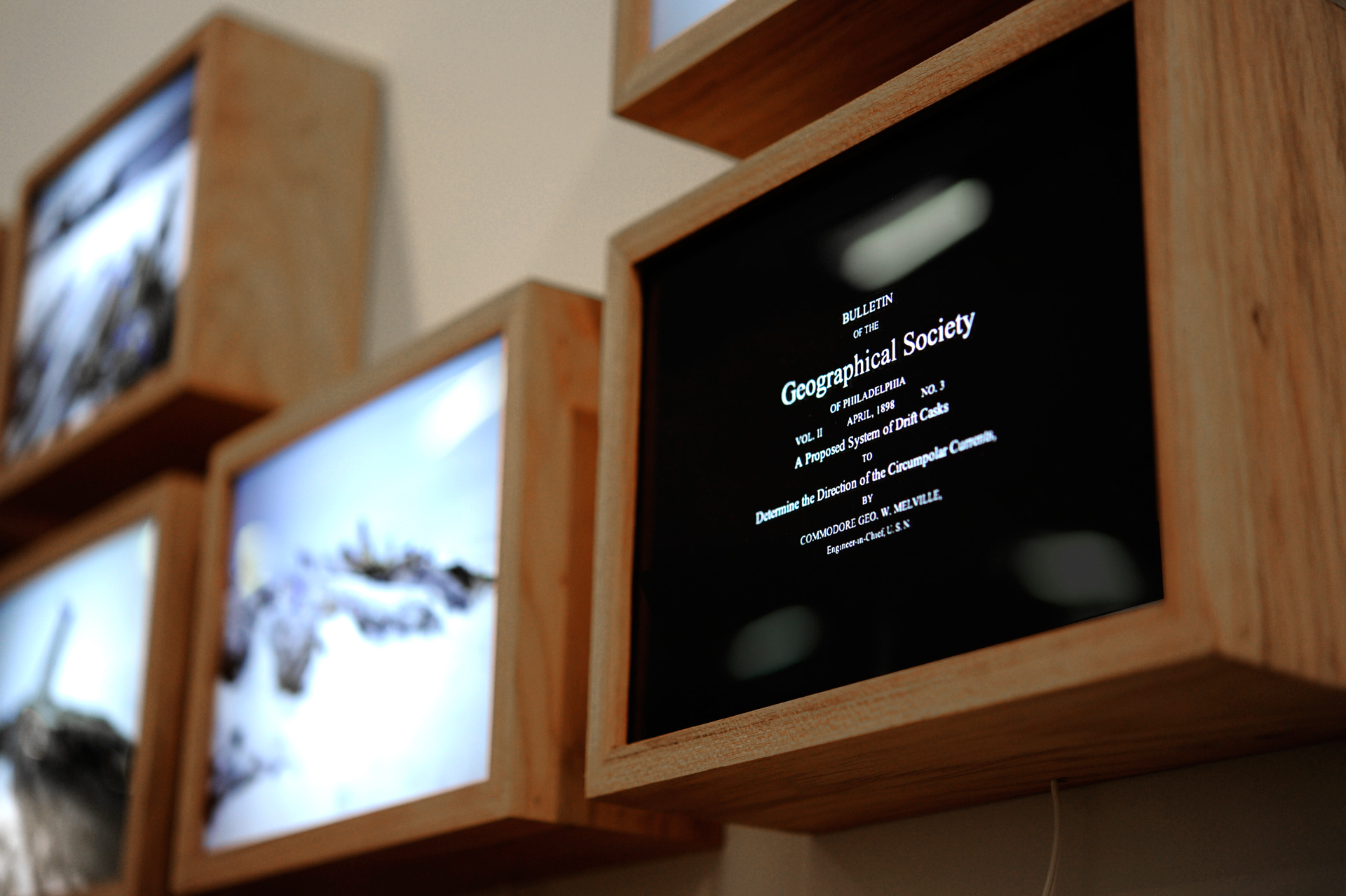

Installation with 26 backlight wood boxes, plexiglass, duratrans, wires and electrical components, LEDs, PVC and aluminum.

220 x 200 x 30 cm

2012

In the end of the XIX Century, the planet’s poles remained the last territories unexplored by men. Adventurers launched themselves to conquer the high latitudes, sacrificing their lives in exchange of their accomplishments, risking themselves in non-guaranteed-return expeditions.

In 1898, the North-American commander Georges Melville published a treaty about the circumnavigation of the North Pole in the Bulletin of the Geographical Society of Philadelphia under the title: A Proposed System of Drift Casks to Determine the Direction of the Circumpolar Currents.

There, he empirically analyses the action of maritime currents that circle the Arctic by using a system called Drift Casks - barrels that remained to drift in the Ocean. The experiment consisted of throwing wood-numbered barrels, close to the Behring Strait and North from Vladvostok, in Siberia and collecting them after a while in another point.

Those barrels were taken by maritime currents crossing all the Arctic Ocean until the East Coast of Greenland and Spitsbergen Island. This theory opened a new perspective of action for the intrepid explorers to reach the magnetic pole. Among these great men, there are Fritjof Nansen and Roald Amundsen.

In September 2011, I was on board on a sail-boat navigating through the North Coast of Spisbergen for an artistic residence. In one of the beaches, I found pieces of faded wood, remain pieces of branch and salt-water-damaged wood beams. A very strange scene for a place in which the closest tree was 3.000 km away.

In 1898, the North-American commander Georges Melville published a treaty about the circumnavigation of the North Pole in the Bulletin of the Geographical Society of Philadelphia under the title: A Proposed System of Drift Casks to Determine the Direction of the Circumpolar Currents.

There, he empirically analyses the action of maritime currents that circle the Arctic by using a system called Drift Casks - barrels that remained to drift in the Ocean. The experiment consisted of throwing wood-numbered barrels, close to the Behring Strait and North from Vladvostok, in Siberia and collecting them after a while in another point.

Those barrels were taken by maritime currents crossing all the Arctic Ocean until the East Coast of Greenland and Spitsbergen Island. This theory opened a new perspective of action for the intrepid explorers to reach the magnetic pole. Among these great men, there are Fritjof Nansen and Roald Amundsen.

In September 2011, I was on board on a sail-boat navigating through the North Coast of Spisbergen for an artistic residence. In one of the beaches, I found pieces of faded wood, remain pieces of branch and salt-water-damaged wood beams. A very strange scene for a place in which the closest tree was 3.000 km away.

I remember Melville’s theories, and Nansen stories, in which it becomes clear of how much can we learn from observing Nature. How much can we learn from local culture, and the inhabits of those who are already familiar with a certain location. I started to outline my research towards the understanding of the world around us. I try to classify and reorganize those remaining portions of vegetal life: I group, pile up, add numbers and tables, tags and coordinates.

As a late disciple of those brilliant men who have been there long ago, I remake all the work, I copy the method and historically link present and past. In an age in which you know where you are through GPS signs it is almost a “modern evil” to come across North Pole’s “traveling trees” e remember their relevance in the context of Polar Exploration. It’s almost like opening a gap in time, in which the artist finds the starting point not of only one, but of a series of ideas and theories, diluted in every field of human knowledge.

This is the proof, that observing the world around us, can take us further than merely to crossover the hemispheres of our imagination. I confess, I wish I had arrived there in 1898.

As a late disciple of those brilliant men who have been there long ago, I remake all the work, I copy the method and historically link present and past. In an age in which you know where you are through GPS signs it is almost a “modern evil” to come across North Pole’s “traveling trees” e remember their relevance in the context of Polar Exploration. It’s almost like opening a gap in time, in which the artist finds the starting point not of only one, but of a series of ideas and theories, diluted in every field of human knowledge.

This is the proof, that observing the world around us, can take us further than merely to crossover the hemispheres of our imagination. I confess, I wish I had arrived there in 1898.

Driftwood

instalação com 26 caixas em backlight de madeira, acrílico, duratrans, fios e componentes elétricos, leds, PVC e alumínio.

220 x 200 x 30 cm

2012

Ao fim do século XIX, os pólos do planeta permaneciam os últimos lugares inexplorados pelo homem. Aventureiros lançavam-se em busca da conquista das altas latitudes, sacrificando suas vidas em troca de seus feitos, arriscando-se em expedições sem garantia de volta.

Em 1898, o comandante norte-americano Geroges Melville escreve um tratado sobre a circunavegação do Pólo Norte, publicando-a no Bulletin of the Geographical Society of Philadelphia com o título de A Proposed System of Drift Casks to Determine the Direction of the Circumpolar Currents, em que analisa empiricamente a ação das correntes marítimas que circundam o Ártico lançando mão de um sistema denominado Drift Casks - barris que ficam à deriva no mar - que consistia em nada mais que lançar ao mar um barril de madeira numerado, perto do Estreito de Behring e ao norte de Vladvosktok, na Sibéria e coletá-los após algum tempo em outro ponto.

Esses barris são levados pelas correntes marítimas e cruzam assim todo o Oceano Ártico até a costa leste da Groenlândia e da ilha de Spitzbergen. Essa teoria abriu uma nova perspectiva de ação para os intrépidos exploradores poderem alcançar o pólo magnético. Entre esses grandes homens encontram-se Fritjof Nansen e Roald Amundsen.

Em setembro de 2011, eu estive em residência artística a bordo de um veleiro que navegava a costa norte de Spitzbergen. Numa das praias visitadas, encontro pedaços de madeira desbotada, restos de galhos e tocos castigados pela água salgada. Algo um tanto estranho para um lugar onde a árvore mais próxima de onde poderiam ter um dia pertencido, fica a não menos que 3.000 km de distância.

Em 1898, o comandante norte-americano Geroges Melville escreve um tratado sobre a circunavegação do Pólo Norte, publicando-a no Bulletin of the Geographical Society of Philadelphia com o título de A Proposed System of Drift Casks to Determine the Direction of the Circumpolar Currents, em que analisa empiricamente a ação das correntes marítimas que circundam o Ártico lançando mão de um sistema denominado Drift Casks - barris que ficam à deriva no mar - que consistia em nada mais que lançar ao mar um barril de madeira numerado, perto do Estreito de Behring e ao norte de Vladvosktok, na Sibéria e coletá-los após algum tempo em outro ponto.

Esses barris são levados pelas correntes marítimas e cruzam assim todo o Oceano Ártico até a costa leste da Groenlândia e da ilha de Spitzbergen. Essa teoria abriu uma nova perspectiva de ação para os intrépidos exploradores poderem alcançar o pólo magnético. Entre esses grandes homens encontram-se Fritjof Nansen e Roald Amundsen.

Em setembro de 2011, eu estive em residência artística a bordo de um veleiro que navegava a costa norte de Spitzbergen. Numa das praias visitadas, encontro pedaços de madeira desbotada, restos de galhos e tocos castigados pela água salgada. Algo um tanto estranho para um lugar onde a árvore mais próxima de onde poderiam ter um dia pertencido, fica a não menos que 3.000 km de distância.

Lembro-me das teorias de Melville e das histórias de Nansen, de como observar a natureza nos traz grandes ensinamentos, de como podemos aprender com a cultura local e os costumes de quem já está habituado ao lugar e começo a traçar a minha pesquisa rumo ao entendimento do mundo que nos cerca. Tento classificar e reorganizar esses restos vegetais: agrupo e empilho, acrescento números e tabelas, tags e coordenadas.

Como um discípulo tardio de tais homens brilhantes que muitos anos antes ali chegaram, refaço todo o trabalho, copio o método e ligo - historicamente - o presente ao passado. Numa época em que saber onde se está através de GPS é quase um “mal moderno”, deparar-me com as “árvores viajantes” do Pólo Norte e lembrar de sua importância no contexto da Exploração Polar, é quase como abrir uma fenda no tempo, onde o artista encontra o estopim de não somente uma, mas de inúmeras idéias e teorias, diluídas por todos os campos do conhecimento humano.

Prova de que observar o mundo ao nosso redor, pode nos levar muito mais além do que simplesmente uma travessia pelos hemisférios de nossa imaginação. Confesso que gostaria de ter chegado lá em 1898.

Como um discípulo tardio de tais homens brilhantes que muitos anos antes ali chegaram, refaço todo o trabalho, copio o método e ligo - historicamente - o presente ao passado. Numa época em que saber onde se está através de GPS é quase um “mal moderno”, deparar-me com as “árvores viajantes” do Pólo Norte e lembrar de sua importância no contexto da Exploração Polar, é quase como abrir uma fenda no tempo, onde o artista encontra o estopim de não somente uma, mas de inúmeras idéias e teorias, diluídas por todos os campos do conhecimento humano.

Prova de que observar o mundo ao nosso redor, pode nos levar muito mais além do que simplesmente uma travessia pelos hemisférios de nossa imaginação. Confesso que gostaria de ter chegado lá em 1898.